Pope Paul VI promulgated the Novus Ordo Missae in 1969, and one year later in 1970 the official revised liturgical books came into force. 200 years prior to the Novus Ordo, King Louis XVI walked up the bloody steps to the guillotine. A king beheaded by his subjects represented a profound shift in the collective psyche of Europe. Christ had assured us that “thou shouldst not have any power against me, unless it were given thee from above” (John 19:11), and for close to two millennia Christendom had held firm in this belief. The kings and queens who sat on the throne deserved allegiance and respect, and so did all other legitimate authority on earth, because such authority came from God. It was inconceivable that an anointed king ruling by divine right could be deposed and killed by commoners and peasants. Kings had been executed before, but this was a unique and revolutionary act that marked the beginning of the modern age.

The political “Right”, those who wanted to preserve the ancien régime, came into existence during the French revolution, as did the revolutionary “Left”. There were no “liberals” and “conservatives” such as we have today. The system was simple. Royalty, clergy, and laity. Three classes with relations to one another. The king ruled, the bishops and priests lead and taught, and the rest obeyed and prayed. This simple notion was fundamentally undermined. The laity began to wonder if divine right was a sham, because the kings blood looked just the same as theirs. Even just the whispers of this event sent shockwaves throughout Europe, and caused a sublime psychological wounds that persists to the present times. Just as the French Revolution changed forever how the people related to their rulers, so the New Mass changed how we relate to God and His Church.

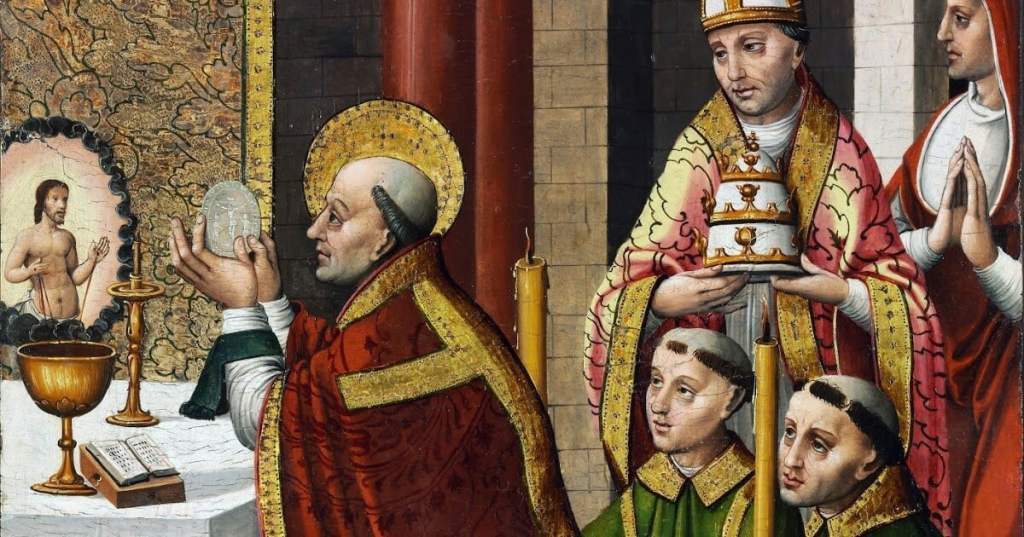

For 2,000 year the Canon of the Mass was sacrosanct. It was inconceivable that these sacred prayers uttered by the Apostles and their Disciples could ever change. If you attended Mass in 1950 your ancestors may have attended a Mass virtually identical for centuries. In a world bubbling with change, the Mass was a timeless anchor that promised to always remain constant. It was the same yesterday as today, and the people on the cusp of the changes would have believed it would remain as such tomorrow and forever.

In our times we can take for granted the liturgical changes and underestimate its weight and impact. All Catholics alive today understand to some degree that their Mass is “new”. There is a spectrum of opinion when it comes to this novelty. Some think the New Mass is the next in an almost unbroken string of changes from the days Our Lord walked the earth, others think there has been an undeniable rupture which has seen the Church turned almost upside down. Whichever position the truth is that the Mass has changed and we accept this as the state of things.

Our ancestors would have had no such experience. For them, the Mass was a living reality which had developed organically through the early centuries, become more or less fixed in the medieval period, been codified at Trent, and was still with them today. At this point we may consider, what was a more significant rupture, the execution of Louis XVI in 1793, or the changes in 1969? I would argue the latter, because they concern God and His worship, and therefore are more profound. The way we worship God strikes to the heart of human psychology. The rule of prayer determines the rule of belief, and vice versa. Both how we believe and how we worship determine how we live, and this last point gives rise to a new principle: as the Church goes, so does the world.

We live in an economy of grace. Every new Saint, every Sacrament received with devotion, every prayer, genuinely improves the world insofar as it brings down new graces from the infinite bounty of God. If the Mass is transformed in a way that bleeds churches of its congregation, that cannot propagate itself to the next generation, what becomes of the world? The world becomes worse or better in accordance with how well we worship God, because the worship of God is the purpose of our existence and the finality of this world. Just like the French Revolution, some consider it good and some bad, but the fundamental point can be agreed upon by all; that the world was transformed. Likewise, the introduction of the New Mass transformed the Church. The fruits of the New Mass are clear. We have seen an unprecedented decline in Church attendance, plummeting belief in fundamentals of Catholic doctrine like the Real Presence, emptying of convents, monasteries, and seminaries, and in general the Catholic Church has lost a great deal of authority in the eyes of many.

By applying the principle that as the Church goes so does the world, we could add to these fruits the chaos of the modern world. Confusion on fundamentals like gender, widespread immorality, the attack on marriage and the family, and to summarise a general return to a more pagan outlook where life is cheap and might is right. Most of all, the enemies of God have assumed almost total power over Europe and the world. We may term this the “post-Christian” era.

Is it unfair, uncharitable, and unkind to claim that the New Mass is in some way to blame for these modern maladies? Many would claim so. But I believe the logic is robust. The Mass is either the most important thing on earth or it is not. The things we do in Mass either impact the world or they do not. A great apostacy of sorts has followed the liturgical changes or it has not. We are now staring square at a post-Christian era or we are not. These statements are either true or not. If they are true, we need to examine why, and we need to do so without fear or prejudice.

Leave a comment